State Supreme Court holds civics contest, hears case involving inmate’s sexual assault

By Robert Cloud

Whether a county can be held liable for a jail inmate’s sexual assault was an issue discussed Monday, Oct. 10, by the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

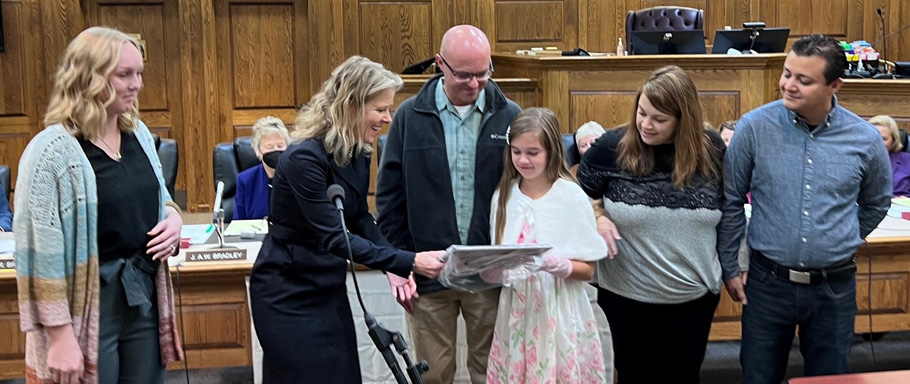

Justices from the state’s high court heard oral arguments at the Waupaca County Courthouse as part of their Justice on Wheels outreach and educational program.

Justice on Wheels gives students, teachers and the public throughout the state an opportunity to observe the court in person.

The state Supreme Court heard two cases locally.

The second case sought the court’s decision on two issues.

First, is Dunn County liable for its failure to address credible allegations that a jail officer was likely to cross a line sexually or romantically with female inmates?

Second, is Dunn County liable for its failure to protect the inmate from a single sexual assault in light of the constitutional risk of being sexually assaulted?

Rachel Slabey v. Dunn County

On March 25, 2016, Deputy Ryan Boigenzahn entered Rachel Slabey’s dorm room at the Dunn County Jail, spoke with her and her cellmate for a “considerable amount of time,” then reached down her pants and touched her genital area.

The dorm room was under video surveillance, but the area where the assault occurred was outside of camera view.

Although Slabey did not immediately report the sexual assault, Boigenzahn was terminated in May 2016 after he failed to report receiving a romantic note from another inmate.

When Slabey learned of Boigenzahn’s termination, she reported the sexual assault that had occurred in March.

On July 18, 2017, Dunn County Circuit Court sentenced Boigenzahn to two years in state prison for second-degree sexual assault by a corrections officer.

The case before the Supreme Court did not directly involve Boigenzahn’s crime, but the county’s liability for allowing the crime to occur.

Slabey sued Dunn County, Sheriff Dennis Smith and other county officials in circuit court, which dismissed her claims on summary judgment.

On July 27, 2021, the state District III Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s ruling, so Slabey appealed to the state Supreme Court.

Plaintiff’s arguments

Christina Wirth, an attorney with Bye, Goff & Rohde of River Falls, represented Slabey before the Supreme Court.

“This case is about Dunn County,” Wirth told the seven justices. “Dunn County knew that Boigenzahn had violated multiple policies regarding proper conduct and what was allowed within the jail.”

Wirth said Dunn County knew Boigenzahn “liked female attention, liked bending the rules and was told he was on a path of escalating misconduct.”

Because of his behavior prior to the assault, Smith considered terminating Boigenzahn, but instead suspended him for three days.

During their arguments, the justices questioned the attorneys.

“One of the things that I remember reading in the briefs that I found concerning is that the bunk that your client was assigned to use was a bunk that was not seen on the video cameras,” Justice Patience Drake Roggensack said. “Was the county (at the administrative level) aware of that?”

“The testimony from Dunn County officials was that they knew that bunk was out of camera view, that the inmates new that bunk was out of camera view and that officer Boigenzahn knew that bunk was out of view,” Wirth replied.

Monell, Section 1983

Justice Rebecca Frank Dallet asked what county jail policy or custom Wirth wanted the court to consider in this case.

The suit against Dunn County is considered a Monell claim under Section 1983.

Section 1983 was enacted by Congress in 1871 to enforce the 14th Amendment at a time when the Ku Klux Klan was terrorizing freed slaves in the South. The federal law allowed citizens to sue state and municipal governments for failure to protect them and hold subordinate officials liable for their actions or inaction.

In Monell v. Dept. of Social Services, the U.S. Supreme Court held that “a local government may not be sued under (Section) 1983 for an injury inflicted solely by its employees or agents. Instead, it is when execution of a government’s policy or custom, whether made by lawmakers or by those whose edicts or acts may fairly be said to represent official policy.”

Wirth said Dunn County can be held liable for a constitutional violation in three cases:

If there is a widespread policy;

If there is a widespread custom;

Of if there is an act by a policy-making official.

The specific act that Wirth pointed to was the sheriff’s decision not to terminate Boigenzahn in 2015 based on the information he had regarding the deputy’s misconduct, Wirth said.

Prior reports on guard’s behavior

Wirth noted that three female inmates had reported about Boigenzahn’s behavior and that security videos showed him touching the inmates inappropriately.

One inmate said other inmates had said Boigenzahn was obsessed with her and that they had seen him standing over her bed watching her sleep.

Wirth said had the sheriff ordered a more through investigation of the female inmates’ allegations, they would have seen that there were several periods of time when he could not be seen on the security cameras.

They would also have learned that he was developing a relationship with an inmate who sent him a sexually graphic photo after her release from jail.

“When I heard those comments that someone is obsessed with you, that they’re watching you when you’re sleeping, it kind of seemed creepy to me and it seemed creepy because there’s potential sexual overtones,” Justice Ann Walsh Bradley said. “Were those ever investigated?”

“They were not and that’s the problem, your honor,” Wirth said.

Wirth noted a number of actions the sheriff could have taken to avoid the sexual assault.

He could have changed Boigenzahn’s shift assignment. Boigenzahn worked the third shift, which did not have a sergeant supervising after 1:30 or 2 a.m. He could have ordered another officer to accompany Boigenzahn during cell checks. He could have alerted the central office where the security camera feeds are monitored to pay closer attention to Boigenzahn.

“All those options were available and deliberately decided against,” Wirth said.

Defendant’s arguments

“In the 150 years since the adoption of Section 1983, federal courts and state courts across the country have been significantly divided on a number of the finer points of Monell law,” according to Dunn county’s attorney, Samuel Hall Jr., with Crivello Carlson S.C., of Milwaukee. “However, there is enough well-settle and well-established law governing Monell to affirm the lower courts here.”

Hall said the courts are looking for conscious conduct or inaction on the part of municipalities in order to hold them liable under Section 1983.

Questioned about the sheriff’s actions after Boigenzahn’s suspension, Hall replied, “There was an investigation, the inmates’ complaints were taken, they were taken seriously, from there a sergeant is directed to review two weeks’ of video.”

He added that a sergeant listened to inmates’ phone calls to see if there was some discussion regarding the guard. “There was nothing.”

At the end of the day, the sheriff had information that there was vague allegations that the officer favored certain female inmates over other female inmates,” Hall said.

“What was vague about those allegations?” Justice Jill Karofsky asked.

“There wasn’t a specific incident,” Hall replied. “What we had was a complaint by one inmate that was seemingly jealous over the fact that Draxler (a female inmate) had contact …”

“How do we know that this inmate was jealous?” Karofsky asked before he could finish his answer.

“Because she was complaining about the favoritism that this officer was allegedly showing Draxler,” Hall said.

“Isn’t that part of the problem with this type of conduct,” Karofsky said. “That you have inmates in a correctional facility who have no power at all, who have to rely on, in this case, a man for their sheer existence and if they do not comply with whatever it is that he wants that there will be a price to pay for that.”

Fraternization policy

Hall said the county jail had a fraternization policy.

Karofsky asked him if the inmates were aware of the policy.

Hall said when they are booked into the jail, inmates receive a pamphlet governing PREA (Prison Rape Elimination Act (which became federal law in 2003). He noted that information covers policies regarding sexual contact and how to report it.

A second pamphlet is posted behind Plexiglass in a common area of the jail.

“After officer Boigenzahn had his three-day suspension was there anything done to increase the level of education to inmates other than what I’m hearing you say is one pamphlet in front of Plexiglass and one pamphlet behind Plexiglass?” Karofsky asked.

“With all due respect, I’m afraid the court is losing sight of Monell,” Hall responded. “Monell requires the lack of action, the utter lack, and in this type of case it is the utter lack of action.”

“With all due respect, I understand what the law says,” Karofsky responded. “After this happened, did sheriff Smith ever designate a PREA coordinator?”

“He did not, but the constitution doesn’t require that,” Hall said.

“Did he ever train staff on what to look for and how to report abuse after the three-day suspension?” Karofsky asked.

“Yes,” Hall said. “There was ongoing training. Officer Boigenzahn had PREA training – you can’t make this up – two days before the assault.”

PREA training

“Let’s talk about that training,” Karofsky said.

She noted that in 2011, Dunn County offered a two-hour training program on sexual harassment and defensive driving.

“An interesting combination,” she said.

Karofsky questioned if the sexual harassment part of the training had anything to do with inmates or if it involved just workplace sexual harassment.

She noted the county offered training on bullying in the workplace and sexual harassment in 2015 and asked if that training involved inmates as well as co-workers.

Hall said the training in which Boigenzahn participated was PREA-related.

Karofsky said she been involved in PREA training while in the Wisconsin Department of Justice.

“The potential victims, that is the inmates in any correctional facility, have got to know how they can safely make reports,” she said. “Is there anything in the record here to indicate that Dunn county had any system whatsoever in place so that inmates in Dunn County Jail could safely make reports of sexual misconduct against the officer who are guarding them?”

“That’s exactly what they did,” Hall said, noting that inmates reporting sexual misconduct led to the 2015 investigation and ultimately to Boigenzahn’s termination.

Constitutional risks

Later, Karofsky noted the similarities between Slabey’s case and the case of JKJ v. Polk County, which also involved a guard sexually assaulting female inmates.

Reading from the JKJ decision, Karofsky said, “The risk of constitutional violations can be so high and the need for training so obvious that the municipality’s failure to act can reflect a deliberate indifference and allow an inference of institutional culpability even in the absence of a similar prior constitutional violation.”

“This case is markedly different than the JKJ case,” Hall said. “There were likely over 100 assaults that occurred over a three-year period.”

Noting that the JKJ language focuses on “a risk of constitutional violation,” Karofsky said, “So whether that risk is to 100 women or one woman, that risk is the same.”

The court will announce its decision on this case at a later date.