Facility has grand plans for future

By Scott Bellile

2017 is a year for the city’s history books, which don’t run in short supply at New London Public Museum.

This year marks a century that New London Public Museum has been expanding the minds of the community with local and natural history, cultural artifacts and more.

New London is home to one of five public museums in Wisconsin. The others are all located in larger cities: Green Bay, Oshkosh, Kenosha and Milwaukee.

“We only have five public museums, five museums that are multi-topic, that encompass history, earth sciences, art, all sorts of topics under one roof, as opposed to an art museum, a historical society, a mustard museum, things that tend to be more focused,” New London Public Museum Director Christine Cross said. “So I think public museums to me are so fascinating because they’re almost like the Cliff Notes of museums: You get little bits of all sorts of different things.”

The museum will mark its centennial with a celebration open to the public on Saturday, Jan. 28, at Crystal Halls Banquet Facility. The event will include a short program on the museum, dinner, dancing, champagne and music by White Chocolate. Tickets are $17 each and on sale at the museum or on its website.

“It’s just a time for the community to come together, have a nice evening in the cold of winter, socialize,” Cross said. “It’s just going to be a really easygoing evening.”

Here is a look at the beginnings of the museum, its major construction project in the 1980s, and where it is today.

The early years

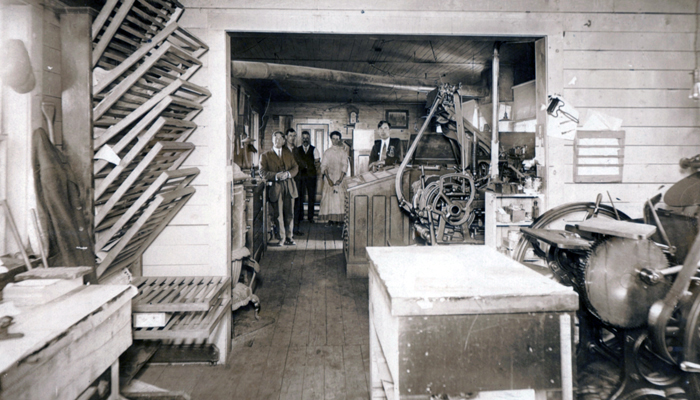

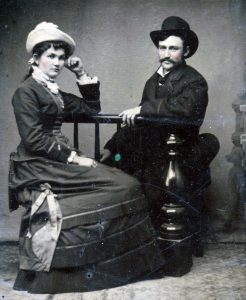

The museum was conceived by Charles Carr, a New York native born in 1857. He became a resident of New London in 1893, the year he started the New London Press newspaper. (This would merge with the Hortonville Star to become the Press Star in 1974.)

New London’s first library opened in Carr’s newspaper office. J.C. Freehoff, then principal of the senior high, lent his books to students and peers. Seeing the need for an official library in town, Freehoff cobbled together 1,031 books and opened the library in 1895. Carr served as librarian, staffing the library two afternoons a week.

When the Press moved offices, the books were housed in various places around town. In 1900, the library moved to the old city hall, and Carr turned it over to the city government. By 1912, the city hall became crowded, so the city council approved the Library Board’s suggestion to build a new library on South Pearl Street using a Carnegie grant. New London Public Library opened in 1914.

On Feb. 6, 1917, the city council resolved to accept Carr’s donation to the city of natural specimens and relics, to be placed inside the library. A grand opening event for Carr’s “museum” held Nov. 8, 1917, featured songs by the high school glee clubs, speeches and a formal presentation.

Quickly citizens began donating their items to the museum to be displayed among Carr’s artifacts in the main library rooms or in the basement auditorium.

Carr traveled the U.S. from time to time securing additions to his collection. He and his wife Emma amassed a collection of natural history items that included rocks, minerals, shells, fossils and taxidermied animals. Emma Carr liked her seashells, accumulating more than 100. Charles Carr took interest in ornithology, recording years of flight information on local birds. He was also an amateur taxidermist.

Carr’s taxidermied birds – including passenger pigeons, ducks, a great blue heron, a long-eared owl and more – remain a major part of the museum today, and donations from other collectors have raised the bird count to more than 200. A hundred years of time have worn down their feathers so today the museum allows patrons to “save the birds” by sponsoring restorations for $75 to $200 per bird.

Deserving credit for the museum’s launch is its first curator, the Rev. Francis Dayton. Carr wasn’t in the best of health when the museum started in 1917, Cross said, so Dayton helped him acquire rare or unique collections and expand the museum’s offerings.

“It was really Francis Dayton that got the museum inventoried,” Cross said. “He’s the one who did the exhibits.”

Charles Carr died in 1923 and Emma Carr in 1924. The Carr estate willed $20,000 to the city to construct a building for the museum’s growing collection. In late 1929, a committee formed to explore the possibility. By July 1931, local architect Victor Thomas had designed the plan and New London Construction Company was building it next to the library. The grand opening was March 16, 1932.

By this time the museum’s collection was more than a natural history hub. It would grow to be a multi-purpose facility documenting local history, natural history, the U.S. military, Native American history and other photographs, documents, ephemera and cultural items.

The 1930s through 1980s were “business as usual,” Cross said, with nothing major to point out other than the community browsed the exhibits and took pride in its hometown museum.

A big undertaking

1986 was an important year for the museum, which until then remained a separate structure from the library.

The museum and library underwent a $752,000 project to join their structures with a 4,600-square foot addition.

Ken Renning, who was president of the Library and Museum Board when the project was approved, said the facilities needed more space for collections, programming and, in the library’s case, the emergence of desktop computers.

Both facilities both lacked handicap accessibility and elevators, and the restrooms were not adequate. Other problems in one building or the other included flooding, deteriorating boilers, outdated electrical wiring and water leakage problems in the walls.

Connecting the similar facilities was a natural fit. In addition, the board explored a number of possibilities to make the proposed building bigger: adding another floor, expanding it east, or buying and demolishing the buildings across the street and starting anew.

Expanding south toward Cook Street wasn’t feasible. Renning said by the time the city acquired the house that stood next to the museum back then, the construction plans were already set. (The house was razed and the lot is used today for outdoor programming.)

The city council and the board held differing opinions on how much money the expansion project deserved, with the council being more conservative.

“It was kind of frustrating,” Renning said. “It really was.”

Ultimately the council authorized one of the cheaper options of connecting the two buildings and redesigning the entrance. Construction got off to a fast start, and the project finished in the late summer.

The space usage within the building was shuffled. Today the library takes up the upper levels of what were the library and museum buildings. The museum takes up less than half of of the lower level.

Serving on the Library and Museum Board at the time of the grand opening were Renning, William Morien, Faith Brown, Dolores Radtke, Virginia Pharr, Ron Steinhorst and Lynn Finch.

Renning wished the board had better luck with convincing the city council to approve a larger expansion because space needs remain an issue today. Still, the board and the community were excited with the progress made. A grand opening ceremony was held Sept. 14, 1986.

“We were very proud of it, very happy, and the people that came through it were kind of excited with what they saw,” Renning said.

Steinhorst serves on the board to this day and recalls the grand opening.

“I still remember the ‘ooohs’ and the ‘aaahs’ of people coming in and seeing the facility when it was brought together at that particular point,” said Steinhorst.

Today and the future

Cross staffs the museum with Assistant Director Alice Gilman and Program Coordinator Wendy Stone. Volunteers also keep it going.

Attendance remains stable compared to what it was around the time of the redesign in the 1980s: 3,500 to 4,500 people a year.

The space crunch prevents Cross from hosting large classes or tour groups, which impacts attendance numbers. On the other hand, she said it’s easier to be flexible with things that larger museums couldn’t be, like organizing small-group tours on specific topics.

Cross said one of the museum’s recent successes is engaging community members with its Facebook page. More than 1,500 people follow the page for information and its popular posts about New London history.

“We have been having so much fun with the Facebook page,” Cross said. “It was important to us to start the Facebook page because we looked at it as another portal for getting the collection out in the public. We don’t have a lot of exhibition space, so we’re trying to find different ways to get more of our stuff that’s in storage on public view. And Facebook is a great way to do it because it doesn’t damage the artifact and it has a wide reach.”

Space has become a major concern over the last decade. Today the museum takes up around 3,000 square feet of the library, less than a quarter of the building. About 800 square feet is office and public research space, which are shared and cramped.

The other 2,200 square feet is exhibit space. Cross estimated only 20 to 25 percent of the museum’s permanent collection can be displayed due to lack of space. Less than 2 percent of the museum’s Native American stone tool collection is on display. Cross clarified that it’s never practice to display 100 percent of a collection because that goes against preserving the objects.

The Library and Museum Board has for some time been exploring constructing a new library and handing the current joined facility over to the museum entirely. Discussions have recently turned to erecting a mixed-use library on the former Wolf River Lumber site along the Wolf River.

Everything is just talk right now, as the funds and official approval from the city council aren’t there.

The museum has already had an architect draw a floor plan for the current building in the event the museum takes over. Plans include 4,500 square feet of exhibition space, an expanded Curiosity Corner for kids, more research space, climate-controlled storage space for items not on display, and a meeting room.

“One of the big concerns the community has had is when the library builds a new library and moves that these historic buildings would be left empty,” Cross said. “We want to assure people that that couldn’t be farther from the truth. The museum is anxious to be able to expand into the space.

“When we’re able to expand, we’ll be more of a destination,” Cross said.

That time may not come for a while, but the museum remains committed to preserving its presence and enriching the lives of anyone who is interested in learning.

“It’s definitely one of the cultural elements that we can brag about … that many other places don’t have,” Steinhorst said.